He was born in Pyongyang, he fought in the Korean War and in 1957 he came to Argentina with 11 other prisoners. His story is intimately linked to the handshake of Kim Jong-un and Donald Trump. Help us find his relatives.

* * *

Sometime in the year 1950, perhaps in August or September, a 20-year-old boy named Kim Kwan Ok marched to the front in the Nakdong River, just at the southern tip of Korea: until a few days ago, this same boy was working in a courtroom, helping with paperwork and the simplest things, earning little money to feed his family. His father had died, and his mother and three younger brothers relied on him.

Kim Kwan Ok did not know how to make a pass or fire a weapon, but he had been forcibly recruited by the communist government of North Korea and had been assigned to an anti-aircraft battery composed of a group of teenagers who were driving a Soviet cannon: the Korean War has just started and would keep the world in suspense for the next three years— and even longer. Its consequences continue to this day.

“That day in the Nakdong River many died, I was lucky,” says Kim Kwan Ok, who is about to turn 89 years old. “I saw it all. God saved me. Many died, some were left without legs, others without arms. It was ugly, very ugly. I was lucky”.

Mr. Kim lives in Buenos Aires. He was born in 1929 in Pyongyang, a city that today is the capital of North Korea, a country that usually appears in the Anglo-Saxon press as the “Hermit Kingdom” because it is the most isolated/isolated/shut-off in the world and escaping is almost impossible. It is also a communist dictatorship embarked on a nuclear race that right now, after its leader Kim Jong-un shook hands with President Donald Trump, seems to have slowed down.

Mr. Kim drinks coffee at a restaurant on Avenida Independencia. He speaks Spanish with Oriental accent and mixes it with frequent smiles. His slanted eyes have become smaller with age and while conversing they get lost in the memories of Korea: his fifteen days in the war, the American planes in the sky, his improvised brown uniform, the soldiers who screamed at night in their dreams “Mom!", the fear and confusion. Mr. Kim does not know anything about his three brothers, who stayed in Pyongyang. Such are the stories of the Korean War.

The war began in 1950, when the communists led by Kim Il-sung (the grandfather of the current North Korean leader) marched south with the help of the Chinese and reached the Nakdong River. They were about to take the entire peninsula when a coalition of 16 countries led by the United States entered to expel them. After three years of fighting, the situation was tied and a ceasefire was signed. But not peace: technically, the two Koreas are still at war until today.

"When the Americans entered, they ordered us to return to the North," Mr. Kim continues. He, who was not a communist nor a military man, did not want to continue fighting. "We were walking through mountain trails. We were a group led by an officer. At a moment, at night, several of us escaped: we were afraid of what could happen to us if they discovered us, but we did it anyway."

Mr. Kim uses gestures when he can’t find the words he is looking for in Spanish. Now he's aiming a rifle, now he’s raising his hands: somewhere in the province of Chungcheong North, a South Korean patrol found the deserters and captured them.

"And I became a prisoner," he continues. "Prisoner of South Korea. They sent me to a prison camp in Busan. We were all from the North and China: all together, 7,000. Half Chinese, half Korean." It was the Geoje-do prisoners war camp.

- How long were you there?

- Three and a half years.

-What was life like in that camp?

- Ugly, ugly! Inside that camp... they killed people! They killed people they did not know and nothing happened. There was no law.

We know the story of Mr. Kim thanks to Lee Kyo Bum, another immigrant like him, who wrote about Korean immigration in Argentina, and published a book with the Sunyoungsa publishing house in Seoul, in 1990. The book tells the odyssey, almost forgotten today, of the twelve North Korean prisoners who arrived in Argentina after the war.

When the conflict ended, in the camp of Geoje-do the prisoners were given the choice to return to North Korea, stay in South Korea or emigrate, with the help of the United Nations, to a neutral country.

Mr. Kim thought he could not return to the North, from whose army he had escaped: "They would have kill me, for sure." But in the South he had no money, no property, no relatives. His life had changed completely.

The repatriation of the prisoners was one of the most delicate points in the armistice signed by the two Koreas in 1953. The Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission, headed by India, oversaw the return of 83,000 North Koreans to the North and the resettlement of another 22,000 in the South. A minority of 88, composed of 76 North Koreans and 12 Chinese, preferred to emigrate. Many wanted to go to the United States, but since it was not a neutral country, they could not. They asked for Mexico, to travel later to the north. But Mexico did not open its doors.

On the other hand, Argentina and Brazil did.

On February 9, 1954, these prisoners left Korea on a ship for their first stop: Madras (now Chennai), in India. From there, after three years in another camp (although less restrictive), they would be transferred to South America.

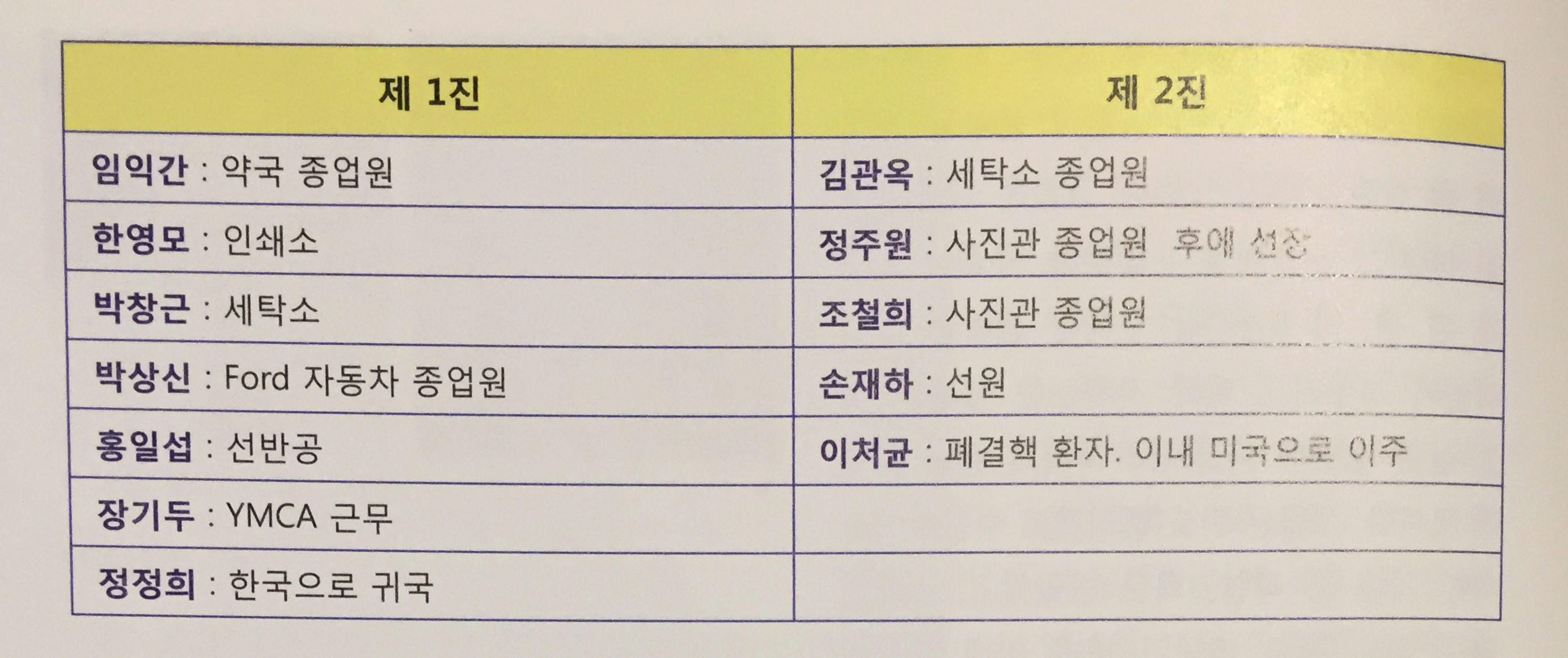

Mr. Kim examines the list of the twelve prisoners who chose to come to Argentina, among whom he finds himself.

- Lim Ik Kan: "He's alive. He has a daughter who lives in Canada. "

- Han Yong Mo: "He went to North America."

- Park Chang Kun: "He is in North America. He lives".

- Park Sang Shin: "I do not know where he is".

- Hong Il Sob: "He's in Korea. I do not know if he is fine. "

- Jang Ki Doo: "I do not know where he is".

- Jung Jung Hee: "I do not know where he is".

- Kim Kwan Ok: "Me."

- Jung Choo Won: "He passed away. He was a ship captain. "

- Cho Chol Hee: "He went to North America. He died".

- Son Jae Ha: "He lived here, but he died. He has two daughters. "

- Lee Cho Kyun: "I do not know where he is".

When he arrived in Argentina, Mr. Kim had a hard time getting a job. But he found a Japanese dry cleaners by chance, "in Viamonte Street, number 366", and he worked there for one year. Then he entered the laboratory of Otto Hess, an optics company with a photography section. Later he got a position as party photographer in La Boca and Barracas neighbourhoods. "I had a Konica camera," he says. "I couldn’t buy a famous machine: I did not have money." Over the years, he also became a public auctioneer and worked in the fields and in a supermarket.

In the meantime he got married, had a son, founded the Argentine-Korean Association and became its first president: Mr. Kim facilitated the resettlement of 2,000 Koreans and was invited later to Seoul, where the South Korean government condecorated him. He then traveled there twice more, also invited.

Over the years, Mr. Kim became a respected man of the Korean community in Argentina: one of his patriarchs.

He only needs to fulfill a mission in his life: to reunite with his family. "In this situation, I do not know if it will happen," he says, with a bit of melancholy. "I'm waiting, but how long? I will have to wait a hundred years, at least. A lifetime. How sad, it's very sad." To this day he continues to dream, sometimes, with his mother. Her name was Hang Su-ok.

- Do you want to go back to North Korea?

- When it's free, I'll go back. When there are no communists, then yes, I will go at once. Not before. If I go, they kill me! Totally, no, won’t go.

- Do you think your brothers are alive?

- I think so. Some of them probably have died, but they are three.

- Do you think your brothers believe that you died in the war?

- Of course, of course! I sent them letters several times. They never answered. The communist government does not allow letters to arrive. For them, I do not exist anymore. But I was here all these years.

Epilogue

The Korean War is a problem in the present time: divided families, like Mr. Kim's, have been distributed throughout the world. And while they can not recover contact, the crime of their partition is still alive.

Telling the full story of the twelve Korean prisoners who arrived in Argentina in 1956 and 1957 will allow us to better understand how the conflict of Kim Jong-un, which may seem strange or distant, is much closer to us than we believe.

Help us find the other 11 Korean immigrants, those men who changed their destiny as prisoners and who in Argentina became pioneers of a strong and struggling Korean community.

If you know something about them or their descendants, please write to [email protected]

We want to know more.